Jules Isaac was one of France’s leading historians and intellectuals when World War II erupted in 1939. The German occupation of France cost him just about everything: He lost his position as the country’s Inspector General of Education and then his wife, daughter, and son-in-law perished in the death camps. The evil perpetrated by the Nazis led him to focus his attention on the roots of anti-Semitism. How could the Jews be so despised, he wondered. By the end of the war his research had resulted in Jesus and Israel, a 600 page manuscript arguing that a particular strain within the tradition of Christian teaching was to blame. His ideas were later published in a simpler English version titled The Teaching of Contempt: Christian Roots of Anti-Semitism. In it he argued that three main themes within Christian tradition were responsible for anti-Semitism.

The first is the idea that the dispersion of Jews after 70 A.D. was God’s punishment for rejecting Jesus as the Messiah. The second is the notion that the Judaism of Jesus’ time was a dead, legalistic religion without any true devotion to God. The third is the charge that the Jews were collectively guilty of committing “deicide” in regards to the crucifixion of Christ and as such have given up all rights to God’s promise in the Old Covenant.

Isaac argued against all three positions based on historical evidence and scripture. His conclusion, as he summarized in a later memorandum, was that “the teaching of contempt for the Jews, in essence anti-Christian, should be purified by being biblically Christian”, faithful to the acts and teachings of Jesus.[1] In other words, there is a strong strain of anti-Semitism within the history of the Church, but that teaching is not truly Christian. Isaac believed that all three of the ideas under-girding anti-Semitism are unbiblical and should be repudiated by the Church.

At the same time that Jules Isaac was wrestling with anti-Semitism, the Vatican’s apostolic delegate in Istanbul during World War II, Archbishop Angelo Roncalli, was hard at work saving Jews from the Nazis. He helped rescue tens of thousands of Hungarian and Slovakian Jews by getting them transported to Palestine and was instrumental in saving 55,000 Jews in Romania. Charles Barlas, director of the Jewish rescue committee in Turkey later lauded Rancalli for his “heroic deeds” and for working “indefatigably on [the Jews’] behalf.”[2]

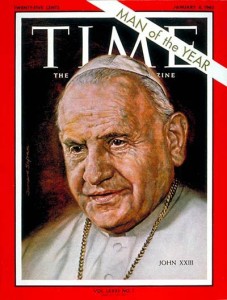

Roncalli was elected Pope John XXIII on October 20, 1958 and very early in his tenure ordered the Latin word perfidis removed from a Good Friday prayer for the Jews. The term described the Jews as “faithless,” although many understood the word in a much more pejorative sense and the Pope wanted those false notions done away with. This was typical of Pope John, who, for example, greeted a group of American Jews with the words “I am Joseph your brother.” Clearly he had a heart for the Jewish people and desired that the family of God be united.

Roncalli was elected Pope John XXIII on October 20, 1958 and very early in his tenure ordered the Latin word perfidis removed from a Good Friday prayer for the Jews. The term described the Jews as “faithless,” although many understood the word in a much more pejorative sense and the Pope wanted those false notions done away with. This was typical of Pope John, who, for example, greeted a group of American Jews with the words “I am Joseph your brother.” Clearly he had a heart for the Jewish people and desired that the family of God be united.

Given the background of the two men, it is no surprise that a June, 1960 meeting of Isaac and Pope John XXIII was one of the driving forces behind the shortest and perhaps most controversial document of Vatican II: Nostra Aetate. Today is the fiftieth anniversary of the opening of that Council and I think that makes it a good time to learn a bit more about the history of this important document and what it teaches about the relationship between the Church and other religions, particularly Judaism. If you are so inclined, you can do just that by clicking here.

[2] Quoted in Dalin, David G. The Myth of Hitler’s Pope: Pope Pius XII And His Secret War Against Nazi Germany. (Washington: Regenery, 2005), 95. For more on Pope Pius see my paper here.