Does the success of the scientific method suggest that the Christian worldview is false? Adam Savage seems to think so. The Mythbusters star gave one of the most popular speeches at this year’s “Reason Rally” in Washington D.C. In it he celebrated the many ways in which science has enabled him to be at the rally.

He noted:

Testable, provable phenomena, and the predictions they allow, big and small, brought me here to in front of you today and they will take me back to my family when I am done. They allowed me to drive to DC on a bus, type my speech on a screen, ride to this rally in a car, walk on shoes that support my feet, and wear clothes and a hat that protects my pale skin from the sun. … Everything that we have that makes our lives possible exists because human beings have tested the things they found in their surroundings, made predictions based on those tests, and then improved upon them.

Savage’s overarching point was that the success of the scientific method at gaining knowledge of the world and enabling man to build cool machines is evidence against the existence of God. This claim is false on several levels.

What Can Science Tell Us about Reality?

First, science (at least as it is currently practiced)[1] may tell us about the material world, but this does not mean that the material world is all that exists or that there is no God. To assert that science has shown there is no God is like a blind man declaring that light doesn’t exist because he cannot see it. If God is not matter, trying to find him using a method that only measures matter could never possibly succeed. Science may be excellent at discovering some facts about the universe, but that does not mean it is the source of all the facts.

This constrained view of science has even been affirmed by the National Academy of Sciences.: [2]

As such, science does not claim any knowledge of whether or not God or angels or souls exist, or even what constitutes the forces of natural law. Isaac Newton understood science in this way. He described what happened to objects under the influence of gravity, for example, but he never offered a theory for what gravity actually is. He saw science as a limited discipline.

Many skeptics simply don’t buy this. For instance, Sam Harris claims that the NAS statement is “stunning for its lack of candor.”[3] Those that agree with Harris think that science provides us with knowledge of all of reality, or at least the parts of reality that we are able to know. They argue that if something is not empirically verifiable than it either doesn’t exist or can’t be “known” as an objective fact. Mitch Stokes points out that, while scientists have followed Newton in many ways, they “haven’t emulated [his] clear understanding that science doesn’t encompass all of reality. Instead, many scientists have shrunk their notion of reality to fit science’s limited reach. If it ain’t science, it ain’t real.”[4] This is called scientism, a term skillfully defined by William Lane Craig and J.P. Moreland:

Many skeptics simply don’t buy this. For instance, Sam Harris claims that the NAS statement is “stunning for its lack of candor.”[3] Those that agree with Harris think that science provides us with knowledge of all of reality, or at least the parts of reality that we are able to know. They argue that if something is not empirically verifiable than it either doesn’t exist or can’t be “known” as an objective fact. Mitch Stokes points out that, while scientists have followed Newton in many ways, they “haven’t emulated [his] clear understanding that science doesn’t encompass all of reality. Instead, many scientists have shrunk their notion of reality to fit science’s limited reach. If it ain’t science, it ain’t real.”[4] This is called scientism, a term skillfully defined by William Lane Craig and J.P. Moreland:

[Scientism is] the view that science is the very paradigm of truth and rationality. If something does not square with currently well-established scientific beliefs, if it is not within the domain of entities appropriate for scientific investigation, or if it is not amenable to scientific methodology, then it is not true or rational. Everything outside of science is a matter of mere belief and subjective opinion, of which rational assessment is impossible. Science, exclusively and ideally, is our model of intellectual excellence.[5]

As such, “there are no truths apart from scientific truths, and even if there were, there would be no reason whatever to believe them.”[6] In my experience, most skeptics who appeal to the scientific method as evidence against Christianity hold to some form of scientism.

The Philosophical Problems with Scientism

We have already seen that scientism does not follow from the fact that science works. The theory also has another logical problem: it is self-defeating. That is to say, the proposition that all knowledge must be gleaned from the scientific method did not itself come from the scientific method, nor could it have. As such, according to its own standard, scientism could not count as valid knowledge.

Put another way, scientism suggests that all valid knowledge must be empirically verifiable; there should be physical evidence to back it up. However, the idea that all knowledge must be empirically verifiable is itself not empirically verifiable. There is no physical data to back up the claim that all claims must have physical data to back them up. Scientism, it turns out, is not scientific.

Another problem for scientism is that the scientific method requires certain philosophical presuppositions in order to function and none of these presuppositions are scientific. In other words, those presuppositions were not derived from science, nor can they be defended with an appeal to science.

For example, scientism assumes that nature is real; it is not a figment of our imagination. In order for a geologist to study a rock, he has to believe that the rock is actually there to study. Also, scientism assumes that people have the ability to reason. Scientists make conclusions based on inference to the best explanation, for instance, which is an intellectual exercise. However, if you ask scientists why we should believe the rock is real or why we should trust our reasoning abilities, they are unable to appeal to science to support their beliefs. These propositions must be defended through philosophy. However, according to scientism, philosophy is not a valid source of knowledge. As such, the presuppositions of science cannot be known to be true and therefore scientism falls in on itself. As Edward Feser notes,

Of its very nature, scientific investigation takes for granted such assumptions as that: there is a physical world existing independent of our mind; this world is characterized by various objective patterns and regularities; our senses are at least partially reliable sources of information about this world; there are objective laws of logic and mathematics that apply to the objective world outside our minds; our cognitive powers – of concept-formation, reasoning from premises to a conclusion, and so forth – afford us a grasp of these laws and can reliably take us from evidence derived from the senses to conclusions about the physical world; the language we use can adequately express truths about these laws and about the external world; and so on and on. Every one of these claims embodies a metaphysical assumption, and science, since its very method presupposes them, could not possible defend them without arguing in a circle. Their defense is instead a task for metaphysics, and for philosophy more generally; and scientism is thereby shown to be incoherent. [7]

Science and the Christian Worldview

If scientism can’t account for science, what can? Christianity. Indeed, the Christian worldview is unique among belief systems in providing the philosophical foundation and motivation for doing science. Christianity alone affirms all of the presuppositions needed for science and can fully account for why science works, including the following, for example.

Nature is Real

Christianity teaches that the physical world is real. Obviously this is a fundamental assumption for studying nature. However, not all worldviews accept this. Hinduism teaches that physical reality is an illusion. Many forms of pantheism teach that all distinctions between particular objects are not real, but only “appearances” of the Absolute, the One. These are not worldviews that lend themselves to scientific study. Why would I try to examine something that isn’t actually there?

Nature is Intelligently Ordered

The biblical worldview also emphasizes that God gave his creation order. Thomas Woods notes that “throughout the Bible, the regularity of natural phenomena is described as a reflection of God’s goodness, beauty, and order.”[8]

The idea that the universe operates according to fixed patterns may seem self-evident to those of us in the West, but it certainly hasn’t been to most cultures of the world. For example, even the ancient Babylonians, who excelled at many aspects of culture, “perceived the natural order as so fundamentally uncertain that only an annual ceremony of expiation could hope to prevent total cosmic disorder”[9] This mindset does not produce science.

The idea that the universe operates according to fixed patterns may seem self-evident to those of us in the West, but it certainly hasn’t been to most cultures of the world. For example, even the ancient Babylonians, who excelled at many aspects of culture, “perceived the natural order as so fundamentally uncertain that only an annual ceremony of expiation could hope to prevent total cosmic disorder”[9] This mindset does not produce science.

Neither does the traditional Chinese view of the world. Although many small gods have been worshiped among the folk religions of China, the intellectual class has generally perceived the world as governed by an impersonal essence. This provides some order to the world but even so does support science. Science needs a rational law that can be discovered. Marxist historian Joseph Needham concluded, after a decades-long search for a materialistic explanation for the lack of scientific advancement in China, that science didn’t develop in China because they didn’t believe in a personal law-giver. He writes: “There was no confidence that the code of Nature’s laws could be unveiled and read, because there was no assurance that a divine being, even more rational than ourselves, had ever formulated such a code capable of being read.[10] Rodney Stark adds, “As conceived by Chinese philosophers, the universe simply is and always was. There is no reason to suppose that it functions according to rational laws or that it could be comprehended in physical rather than mystical terms. Consequently, through the millennia Chinese intellectuals pursued ‘enlightenment,’ not explanations.”[11]

Science requires an ordered and rational universe. Christianity teaches just that, while other worldviews simply do not.

Nature is Good

Christianity also teaches that the material world is good and has been given to man to govern. Within a biblical worldview, working hard to learn about and use the earth for God’s glory has dignity and shouldn’t be avoided. Again, this is hardly a universal approach to nature.

In many cultures, the material world is equated with evil and chaos. In others, it is a deadly trap from which we should strive to escape. As such, manual labor is denigrated and relegated to the lower castes of society. For example, it has been suggested by historians that one reason the Greeks did not develop an empirical science is that they didn’t want to get their hands dirty. The experimentation and empirical study inherent in science requires the type of work that the Greeks thought only slaves should do. [12]

Nature is not Divine

While the Christian worldview teaches that nature is good, the Bible is also very clear that nature is not a God, nor does God inhabit nature. This provides a clear distinction from many animistic pagan religions and provides another necessary foundation for science. As Indian scholar Vishal Mangalwadi notes,

A culture may have capable individuals, but they don’t look for ‘laws of nature’ if they believe that nature is enchanted and ruled by millions of little deities like a rain god, a river goddess, or a rat deva. If the planets themselves are gods, then why should they follow established laws? Cultures that worship nature often use magic to manipulate the unseen powers governing nature. They don’t develop science and technology to establish ‘dominion’ over nature. Some “magic” may seem to “work,” but magicians don’t seek a systematic, coherent understanding of nature.[13]

Christianity, on the other hand, de-deifies nature. Genesis 1 makes clear that God is not part of nature, nor is he just one of many other capricious gods. This is essential for science. As Nancy Pearcey and Charles Thaxton point out, “The monotheism of the Bible exorcised the gods of nature, freeing humanity to enjoy and investigate it without fear. When the world was no longer an object of worship, then – and only then – could it become and object of study.”[14]

Man has the Ability to Reason

We noted above that science presupposes that man has the ability to gather knowledge and reason from a premise to a conclusion. It takes rationality to observe and then infer to the best explanation, which is perhaps the key element of the scientific method. The Christian worldview has no problem with this; it supports, encourages and celebrates reason. Christianity teaches that God gave us a mind like his own and that we are to cultivate it to more effectively know God and govern his creation. As such we can put confidence in human logic and reason. Mangalwadi points out that this theological assumption bore much scientific and intellectual fruit as Christianity grew:

We noted above that science presupposes that man has the ability to gather knowledge and reason from a premise to a conclusion. It takes rationality to observe and then infer to the best explanation, which is perhaps the key element of the scientific method. The Christian worldview has no problem with this; it supports, encourages and celebrates reason. Christianity teaches that God gave us a mind like his own and that we are to cultivate it to more effectively know God and govern his creation. As such we can put confidence in human logic and reason. Mangalwadi points out that this theological assumption bore much scientific and intellectual fruit as Christianity grew:

Much before the birth of the modern age, the medieval Augustinian monasteries began doing something that became unique to Christianity. When a young man devoted his life to seek and to serve God, the monastery required him to spend years studying the Bible, languages, literature, logic, rhetoric, mathematics, music, theology, philosophy, and practical arts such as agriculture, animal husbandry, medicine, metallurgy, and technology. Thus, the monastery – which was an institution for cultivating the religious life – began producing a peculiarly rational person, capable of researching; writing books; developing technology and science; developing capitalism; and developing complex, rational legal and political systems. The Bible became the ladder on which the West climbed the heights of educational, technical, economic, political, and scientific excellence.[15]

The reliability of reason is an essential presupposition for science. However, once again, this belief is simply missing from many worldviews.

For example, Buddhist and Hindu monks have been around much longer than the Christians and are certainly not less intelligent. Why did this kind of science not develop in Eastern monasteries? Because the Eastern worldviews do not allow for it or encourage it. These systems are, in fact, often anti-reason. The principle of Transcendental Meditation, for example, “is not to know truth, but to empty one’s mind of all rational thought – to ‘transcend’ thinking. To think is to remain in ignorance, in bondage to rational thought.”[16]

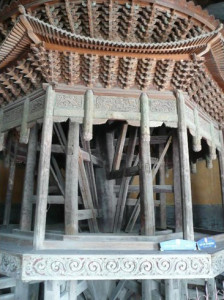

Some might respond that Asian cultures developed very advanced technology and gathered knowledge in books independent of Christianity. This is true, as far as it goes. For example, by the 9th century Chinese monasteries had so many books they had invented rotating bookcases, many of which rotated day and night. Did they turn so consistently because so many people were reading? Not at all. The monks were using the sound of the bookcases as a mantra. A mantra is a sound without sense. It is the opposite of a word (logos) which is a sound with sense. By mediating on the sound of the sacred text turning, the monks hoped to empty their minds of all thoughts and words.[17] A culture of science is simply not going to develop in that worldview context.

Some might respond that Asian cultures developed very advanced technology and gathered knowledge in books independent of Christianity. This is true, as far as it goes. For example, by the 9th century Chinese monasteries had so many books they had invented rotating bookcases, many of which rotated day and night. Did they turn so consistently because so many people were reading? Not at all. The monks were using the sound of the bookcases as a mantra. A mantra is a sound without sense. It is the opposite of a word (logos) which is a sound with sense. By mediating on the sound of the sacred text turning, the monks hoped to empty their minds of all thoughts and words.[17] A culture of science is simply not going to develop in that worldview context.

Ironically, another worldview that can’t support reason and science is the one that most often claims to be their champion: philosophical naturalism. [18] This is the view that matter is all that exists and the universe is basically a closed system of mechanistic cause and effect. It is held by people such as Richard Dawkins (Founder of The Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science) and Sam Harris (CEO of Project Reason, “a nonprofit foundation devoted to spreading scientific knowledge and secular values in society”).

Here’s the problem with philosophical naturalism: if matter is all there is, humans do not have spirits (or any other non-physical characteristics). Therefore, a man is his body, his mind is his brain, and all his thoughts and ideas are only physical phenomena, nothing more. As atheist philosopher Daniel Dennett explains “we now understand that the mind is not, as Descartes confusedly supposed, in communication with the brain in some miraculous way; it is the brain.”[19] You don’t “think” or “believe” or “feel” and the like. Indeed, there is no such thing as a non-material you to do anything at all. There is just a conglomeration of protons and neutrons and such that react to various stimuli in various ways. In this view “consciousness” and “mind” (intentions, desires, beliefs, etc.), along with ideas like “free will” and “self” “can be reduced to whatever the neurons happen to be doing.”[20]

This view undercuts the scientific enterprise in that it makes reasoning impossible and truth unknowable.

Within a Christian worldview, you are not your body; you are a person with a body. When your body dies, your identity is not lost; it carries on without your body. The spiritual element of the person is necessary for rationality, because it is necessary to transcend nature in order to study and think about it. Purely physical things do not reason. A rock cannot think about what it means to be a rock, for example.

So from a Christian perspective, I could explain what is happening right now this way: You are reading the words that I wrote and thinking about the ideas that I am presenting here. You are interacting with physical objects that symbolize abstract concepts and you are evaluating them according to other immaterial standards using your intellect and will, neither of which is made of matter.

However, according to a materialist worldview, that is not what is happening. Rather, the mass of protons and neutrons and such that makes up the body known as “you” is receiving stimuli from the light bouncing off the dots on this screen and reacting to it in a way that produces a sensation referred to as “thinking.” This “thinking” is not really choosing between alternate ideas or weighing various options, though, as if something immaterial was taking place and there was actually more than one possible outcome. Rather it is the process by the brain produces the one output that was possible given the specific physical determiners in place. The idea that “you” are “thinking” is ultimately an illusion. This is not reasoning in any commonly understood sense of the term. It is more like what happens when a thermostat switches on.

However, according to a materialist worldview, that is not what is happening. Rather, the mass of protons and neutrons and such that makes up the body known as “you” is receiving stimuli from the light bouncing off the dots on this screen and reacting to it in a way that produces a sensation referred to as “thinking.” This “thinking” is not really choosing between alternate ideas or weighing various options, though, as if something immaterial was taking place and there was actually more than one possible outcome. Rather it is the process by the brain produces the one output that was possible given the specific physical determiners in place. The idea that “you” are “thinking” is ultimately an illusion. This is not reasoning in any commonly understood sense of the term. It is more like what happens when a thermostat switches on.

Thus, materialism makes the concept of truth incoherent and the knowledge of truth impossible. If all “our” “thoughts” are simply neurological reactions, there is no reason to assume that the content of those thoughts are veridical. On what basis would the experience of seeing a tree, for example, be considered real? How could it be confirmed that the tree objectively exists? Or that the “ideas” present in a brain about that tree are accurate? If everything can be reduced to physical processes, there simply wouldn’t be a way to judge.

Indeed, the notion that physical processes produce accurate thoughts is counter-intuitive. It doesn’t match up with our experience. Generally, the more plausible it is that a person’s ideas are the result of physical processes rather than intellectual reflection, the less trustworthy we consider them. For example, who you would trust more to give you accurate directions in an unknown city: The guy laying on the sidewalk who is obviously under the influence of drugs and alcohol or the very sober soccer mom grabbing some groceries from the market?

The fact is, we usually take what a person says with a grain of salt if we think they are overly tired or sick or under some other physical influence. If a person is completely physical, no words, thoughts, and ideas would be trustworthy. As C.S. Lewis wrote, “If minds are wholly dependent on brains, and brains on biochemistry, and biochemistry (in the long run) on the meaningless flux of the atoms, I cannot understand how the thought of those minds should have any more significance than the sound of the wind in the trees.”[21]

Philosophical naturalism simply can’t account for the scientific method in that it can’t account for reason or the trustworthiness of our thoughts. Christianity, on the other hand, certainly can.

Christianity and the Rise of Scientific Culture

We have seen that other worldviews don’t offer the philosophical foundation or motivation for science to develop, at least not on a society-wide scale. That is exactly why science as we know it didn’t develop within these belief systems.

The fact is that science as we know it grew in the Christian West, specifically because it was the Christian West. While other cultures have produced some good scientists, a culture of science is unique to Christendom because, as we have seen, science needs the theological and philosophical underpinning that Christianity provides. Other cultures don’t just naturally do science. As Pearcey and Thaxton point out, “The type of thinking known today as scientific, with its emphasis upon experiment and mathematical formulation, arose in one culture – Western Europe – and in no other.”[22] Mangalwadi adds:

The global spread of Western education made this scientific way of seeing nature so common that most educated people do not realize that the scientific outlook is a peculiar way of observing the world— an objective (“secular”) method molded by a biblical worldview. Science uses objective methods to observe, organize, and understand the natural world. But this perspective is neither “natural,” “universal,” nor “common sense.” It is a peculiar way of viewing things. Europe did not stumble upon the scientific method through random trial, error, and chance. Some individuals in the ancient world may have looked at nature with a scientific outlook, but their perspective did not become a part of their intellectual culture. The scientific perspective flowered in Europe as an outworking of medieval biblical theology nurtured by the Church. Theologians pursued science for biblical reasons. Their scientific spirit germinated during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries and blossomed after the sixteenth-century Reformation—after Europe became a more literate place, where people could read the Bible themselves and become consciously biblical. [23]

The Middle Ages have often been caricatured as a time of ignorance and superstition, but as extensive scholarship has recently shown, the facts just don’t bear this out.[24] The supposed war between science and religion is actually a recent invention fabricated by those hostile to Christianity. [25] The truth is that, while it was not the only factor, the Christian worldview encouraged and supported the development of science as we know it today. Indeed, science is practiced today only as scientists presuppose (perhaps unwittingly) certain Christian beliefs about reality. Physicist Paul Davies points out:

It was from the intellectual ferment brought about by the merging of Greek philosophy and Judeo-Christian-Islamic thought that modern science emerged, with its unidirectional linear time, its insistence on nature’s rationality, and its emphasis on mathematical principles. All the early scientists such as Newton were religious in one way or another…In the ensuing 300 years, the theological dimension of science has faded. People take for granted that the physical world is both ordered and intelligible. The underlying order in nature – the laws of physics – is simply accepted as a given, as brute fact. Nobody asks where the laws come from – at least they don’t in polite company. However, even the most atheistic scientist accepts as an act of faith the existence of a law-like order in nature that is at least in part comprehensible to us. So science can proceed only if the scientist adopts an essentially theological worldview.[26]

Conclusion

Skeptics often view the relationship of science and Christianity as one of hard facts vs. superstition or reason vs. irrationality. We have seen in this post that the truth is just the opposite. The Christian worldview not only welcomes rationality and scientific investigation of the world, it has been the premier driving force in history behind those endeavors. The fact that science works is not an evidence for atheism, it is one more piece of data that supports a Christian worldview. Adam Savage was thankful that scientists built an airplane that could fly him to D.C. for a speech. He should also be grateful that the Christian worldview built a culture that enabled that engineering feat.

Donald Johnson is the author of How to Talk to a Skeptic: An Easy-to-Follow Guide for Natural Conversations and Effective Apologetics

[1] “Science” has not always confined itself to studying matter, but for our purposes that definition of the term will suffice. For more on the metaphysical sciences, of which theology was the queen, see The Last Superstition by Edward Feser and From Aristotle to Darwin and Back Again by Etienne Gilson.

[2] Quoted in Sam Harris, Letter to a Christian Nation, 63, also available at http://www.nationalacademies.org/evolution/Compatibility.html

[3] Harris, 63

[4] Mitch Stokes, A Shot of Faith to the Head, 129

[5] J. P. Moreland and William Lane Craig , Philosophical Foundations for a Christian Worldview , 346-347

[6] Ibid.

[7] Feser, 84

[8] Thomas E. Woods, Jr., How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization, 75

[9] Woods, 78

[10] Joseph Needham, The Grand Tradition quoted in Nancy Pearcey and Charles Thaxton, The Soul of Science: Christian Faith and Natural Philosophy, 29

[11] Rodney Stark, The Victory of Reason: How Christianity Led to Freedom, Capitalism, and Western Success, 16

[12] Pearcey and Thaxton, 22

[13] Vishal Mangalwadi, The Book that Made Your World: How the Bible Created the Soul of Western Civilization, 220

[14] Pearcey and Thaxton, 24

[15] Vishal Mangalwadi, Truth and Transformation: A Manifesto for Ailing Nations, 119

[16] Ibid, 44

[17] Ibid. Here Mangalwadi references research done by a Buddhist monk named Yeh Meng-te.

[18] I am here using this term quite broadly. For more specific explanations of the various views within a naturalistic worldview, particularly as they relate to the “Mind-body problem”, see Chapter 5 of The Spiritual Brain: A Neuroscientist’s Case for the Existence of the Soul by Mario Beauregard and Denyse O’Leary

[19] Daniel C. Dennett, Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon, 107

[20] Beauregard and O’Leary, 106

[21] C. S. Lewis, Weight of Glory, 139

[22] Pearcey and Thaxton, 17

[23] Vishal Mangalwadi, The Book that Made Your World: How the Bible Created the Soul of Western Civilization, 223

[24] This work was pioneered by historian Pierre Duhem in the early twentieth century. See Chapter 1 in Pearcey and Thaxton’s The Soul of Science and Chapter 5 in Woods’ How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization for a nice summary.

[25] See Pearcey and Thaxton, 19 and Colin Russell, Cross Currents: Interaction Between Science and Faith, 190-96

[26] Paul Davies, “Design in Physics and Cosmology,” in God and Design: The Teleological Argument and Modern Science, ed. Neil A. Manson, 148